At the end of the 19th century, while Europe hummed to the relentless rhythm of machines and triumphant industrialisation, an artistic movement blossomed like an unexpected flower in a garden of coal, iron, and steel. Art Nouveau, born around 1890 and flourishing until about 1910, was that reforming burst of life — a hymn to organic nature in defiance of mechanical rigidity. Drawing inspiration from the sinuous curves of plants and the free forms of living things, this style transformed art in all its expressions into a joyful celebration of nature itself.

At the very heart of this aesthetic, flowers — ever-present motifs — symbolised renewal, the vibrant pulse of spring, and a harmonious union between the senses and the world.

Inspired by the sinuous curves of plants and the free, living forms of nature, the style turned art, in all its expressions, into a joyful celebration of the natural world.

Floral Secrets Unveiled Within the Lines of Art Nouveau

- The Botanical Escape: How artists championed the Iris, the Lily, and the Rose as floral sanctuaries against the cold, gray austerity of the industrial age.

- The Language of Arabesques: Deciphering the symbolism whispered through asymmetrical curves and “whiplash” motifs that breathe organic life into inanimate objects.

- Masters of the Floral Touch: An encounter with Émile Gallé, René Lalique, and Alphonse Mucha—visionaries who transformed glass, precious metals, and lithography into extraordinary herbaria.

- Architecture in Bloom: A journey through the Great Cities to witness how stone vines and botanical stems conquered the urban landscape, from Paris to Barcelona.

- An Enduring Legacy: The lingering echo of these organic silhouettes in contemporary art and modern decor, serving as a timeless tribute to the essential beauty of Nature.

Floral Motifs: The Beating Heart of Art Nouveau

Why did flowers hold such a central place in Art Nouveau? At a time when factories belched smoke and the straight lines of technical progress reigned supreme, artists sought refuge in the fluid grace of nature.

Floral motifs — slender irises, majestic lilies, exotic orchids, or delicate poppies — were never mere ornaments; they embodied an entire philosophy.

These curving, asymmetrical forms evoked life in constant motion.

Symbolically, flowers stood for the eternal cycle of birth, blossoming, and gentle fading — a cycle so often entwined with femininity and sensuality.

Influenced by the century’s botanical discoveries and by the Japanese ukiyo-e prints — with their stylised, ethereal flowers — the creators of Art Nouveau saw in petals an endless source of inspiration.

The iris, for instance, symbolised both purity and mystery, while the rose — with its intertwined thorns — brought a touch of passionate drama. The water lily, floating serenely on the water’s surface, embodied fluidity and harmony, echoing the Impressionist canvases of Monet.

Thus, flowers were never frozen in place: they melted into the lines, creating a vine-like effect — those undulating curves that breathed life into once-inert objects.

Microscopic Influence and the New Botanies: This organic impulse was nourished by the blossoming of scientific botany. Works such as Ernst Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms in Nature) popularized the study of cellular patterns and the microscopic structures of ferns. Within these depths, artists discovered a new pantheon of forms, transforming the rigorous study of nature into an infinite catalog of sacred arabesques.

Iconic Artists and Masterpieces: Petals Made Immortal

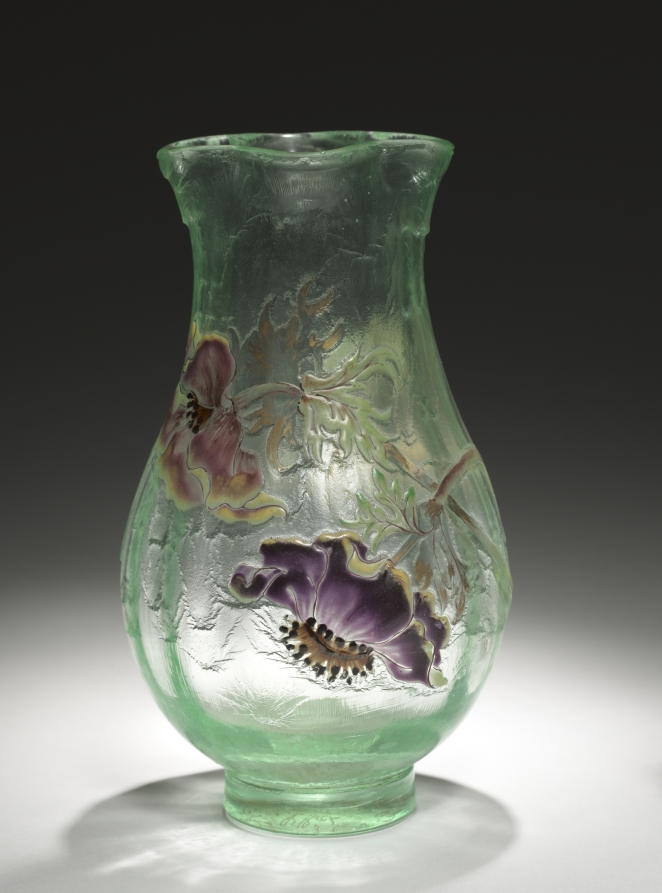

Émile Gallé, the glassmaker from Lorraine and passionate botanist, carried floral art to its very zenith with his famous “speaking vases”.

Using innovative techniques — multilayered glass with motifs revealed by acid etching — he incorporated exotic orchids or anemones in relief, creating the breathtaking illusion that petals were gently pulsing beneath the surface.

His creations, often engraved with poems, celebrated nature as a living muse, deeply steeped in the literary symbolism of the era.

René Lalique, the French jeweller and glassmaker, turned flowers into precious jewels.

His anemones bracelet with translucent petals wove together gold, enamel, and glass to capture a fleeting, almost breath-taking delicacy.

A profound influence on fashion, his pieces carried a sensuality that bordered on the erotic — flowers here became symbols of temptation and mystery.

Many masters of Art Nouveau made flowers the very cornerstone of their work, transforming them into timeless symbols.

Alphonse Mucha, the Czech artist who settled in Paris, remains one of the most radiant examples.

His advertising posters — especially those created for the divine Sarah Bernhardt in La Dame aux Camélias — portray ethereal women wrapped in swirling floral garlands. Petals intertwine with flowing hair and liquid gowns, forming an organic whole where nature and the human form become one.In his celebrated series “The Seasons”, the flowers change with the cycles: luxuriant roses for summer, fading chrysanthemums for autumn — a tender reminder of life’s fleeting beauty.

Other figures further enrich this panorama: Victor Horta, the Belgian architect, wove floral motifs into his buildings. In the Hôtel Tassel in Brussels, for instance, the staircases curl like ivy stems, climbing and unfurling with effortless grace.

Gustav Klimt, in Austria, wrapped his figures in golden floral mosaics in paintings such as The Kiss, merging eroticism and nature in a swirling whirlwind of petals.

Floral Motifs in Daily Life: From Art to the Everyday

The Forerunner: The Shadow of the Arts & Crafts Movement: Art Nouveau drew deeply from the wells of the English Arts & Crafts movement and the vision of William Morris. By championing a return to craftsmanship in defiance of industrialization, this movement paved the way with intricate motifs of intertwined Thistles and Bindweed. This very soil allowed the more audacious forms of the Continent to flourish and come into full bloom.

Art Nouveau did not confine itself to painting or sculpture; it seeped into every domain, carrying its petals gently into the fabric of everyday life.

In architecture, Antoni Gaudí in Barcelona turned Casa Batlló into a true floral masterpiece: its undulating balconies resemble gigantic petals, while the façade itself feels like a wave of sea-flowers gently breaking over stone.

In Paris, Hector Guimard’s celebrated Métro entrances — with their wrought-iron stems and corolla-shaped lamps — brought art to the people, turning the city’s streets into a vast public garden.

In the decorative arts, Louis Majorelle crafted furniture inlaid with floral motifs in precious woods, where slender irises curl gracefully along the armrests and seem to embrace anyone who sits.

William Morris’s wallpapers — the great English forerunner — profoundly influenced the movement with their intertwined vegetal patterns, championing a return to craftsmanship in defiant protest against mass production.

Fashion and jewellery eagerly embraced these themes too: the flowing Liberty & Co. dresses, adorned with delicately printed petals, brought lightness and joy to the feminine silhouette.

In graphic design, advertising posters and illustrations — whether for perfumes or theatre shows — framed their messages with natural floral borders, making art both accessible and irresistibly seductive.

Today, this legacy lives on: from sleek modern logos to stylised tattoos, and even in films such as Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge!, where floral motifs still whisper a sensual, nostalgic dream.

The Legacy

Art Nouveau bloomed only for a moment, yet its intense, fleeting song still echoes — a long, tender poem against the machine, whispering that beauty will always belong to the curves of nature.

Its floral motifs were far more than a style; they were a philosophy:

a gentle call to bring humanity back into harmony with its surroundings, to celebrate organic life in a world growing ever more artificial.

In our own time, when so many of us worry about the fate of nature, these petals from yesterday return like a quiet, poetic reminder.

Like a single petal drifting slowly to the ground, Art Nouveau faded away, yet its roots still nourish contemporary art.

To truly feel its soul, simply pause and look at a flower in your garden: in its delicate, curving veins you will discover the very heart of the movement.

And if the desire takes you, step into the Musée d’Orsay in Paris or the Horta Museum in Brussels – there, the petals of history will open for you once more.

History does not end with this single petal…

A new path now unfolds before you: continue your journey by exploring the destinies of other blossoms that have shaped our world.

Explore our themes through the “Flower Collection” tab, or return to the heart of our world:

GatewayWhat is Art Nouveau?

Art Nouveau is an international art movement that flourished between 1890 and 1910 as a poetic reaction to industrialization. Like “an unexpected flower in a garden of coal, iron, and steel,” it celebrates sinuous lines, organic forms, and floral motifs across architecture, jewelry, furniture, and decorative arts.

What are the typical floral motifs in Art Nouveau?

Iris, lily, rose, water lily, orchid, and ivy dominate, characterized by asymmetrical curves and dynamic “whiplash” lines. They symbolize sensuality, mystery, and the eternal cycle of life.

Who are the major figures of Art Nouveau?

Key artists include Émile Gallé (glass vases), René Lalique (floral jewelry), Alphonse Mucha (posters), Hector Guimard (Paris metro entrances), Victor Horta, and Antoni Gaudí.

What are the most famous Art Nouveau works?

Iconic examples are Hector Guimard’s Paris metro entrances, Émile Gallé’s “speaking vases,” René Lalique’s dragonfly and flower jewels, Alphonse Mucha’s theatrical posters, and Gaudí’s Casa Batlló in Barcelona.

Why is Art Nouveau still inspiring today?

Its flowing floral motifs and organic curves continue to influence contemporary fashion, graphic design, tattoos, and digital art, reminding us of nature’s beauty in an increasingly mechanical world.