Flowers and Art

Flowers and Art: From Painting to Poetry

To the Articles

The flower is arguably humanity’s oldest and most faithful muse. Long before writing was used to record our thoughts, floral motifs adorned Neolithic pottery and Egyptian frescoes. But why has this fascination endured for millennia? It is because the flower embodies the ultimate paradox of existence: absolute beauty, tragically condemned to fade. Within this category of “Pétales d’Histoire,” we invite you to explore this uninterrupted dialogue between nature and human genius—a scholarly journey where each chapter reveals how sap became pigment, and fragrance became poetry.

I. Visual Arts: Capturing the Fleeting Nature of the Living

1.1. Painting: From Allegory to Pure Sensation

For centuries, painting a flower was never a trivial act. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the garden was a closed space, often sacred. A white lily was not merely a garden plant; it was the symbol of virginal purity. However, it was during the 17th century—the Dutch Golden Age—that floral painting earned its prestige as an independent genre.Masters such as Jan Brueghel the Elder or Rachel Ruysch composed bouquets with surgical precision. Yet, these works were “Vanitas.” By including an insect nibbling a leaf or a withered petal, the artist reminded the viewer that wealth and beauty are perishable. These paintings were silent meditations on death ($Memento\;Mori$).The 19th century brought a radical revolution. With the advent of Impressionism, the flower was no longer a symbol; it became a vessel for light. In his garden at Giverny, Claude Monet did not paint water lilies for their botanical significance, but for the way they reflected the sky and water at different hours of the day. The flower thus became the engine of modern abstraction.

1.2. Botanical Illustration: The Marriage of the Scalpel and the Brush

There was a time when art had a vital mission: the pursuit of knowledge. Before photography could freeze reality, botanical illustrators were the eyes of science. This discipline required ironclad rigor: one had to represent a plant with such exactitude that a scholar on the other side of the world could identify it, without sacrificing the elegance of the line.We cannot discuss this field without honoring Pierre-Joseph Redouté. Known as the “Raphael of Flowers,” he navigated the political storms of France, from Marie-Antoinette to Empress Joséphine, leaving behind “Les Roses”—a monumental work where every plate is a technical masterpiece of watercolor. These illustrators did not just paint plants; they invented a visual heritage that allowed for the classification of life and the dreaming of distant lands.

II. Flowers in the Narrative Arts: An Eternal Metaphor

2.1. Poetry and Literature: The Word That Never Fades

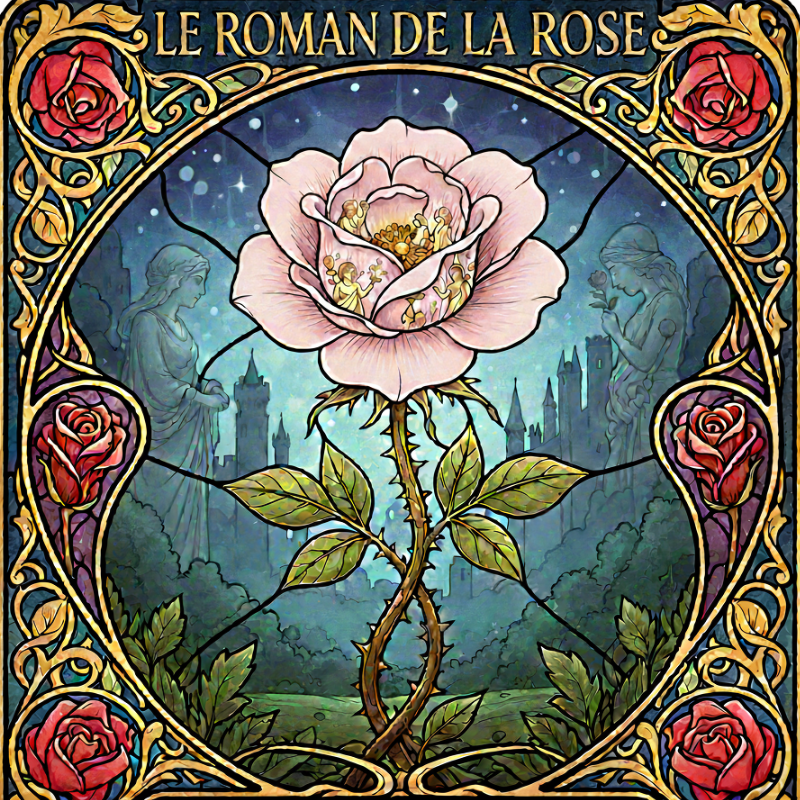

While the painter uses color, the writer uses symbols. In literature, the flower is a character in its own right, a powerful narrative tool.For the poets of the Pléiade, such as Pierre de Ronsard, the rose is a life lesson. The famous “Mignonne, allons voir si la rose…” is not just a gallant invitation; it is a plea to live urgently in the face of time’s brevity. Conversely, for the Romantics, the flower became a mirror of the tormented soul. A simple cornflower or an isolated sprig of heather was enough to embody the solitude of the traveler.The 19th century marked a turning point with Charles Baudelaire and “Les Fleurs du Mal” (The Flowers of Evil). Here, the flower detaches itself from the pastoral countryside to become urban, sometimes venomous—a metaphor for beauty extracted from suffering and decay. Literature teaches us that the flower is not always gentle; it can be cruel, mysterious, or fatal.

2.2. Theater and the Novel: The Object That Reveals

In the classic novel or theater, the flower is often a plot catalyst. A forgotten bouquet, a flower pressed between the pages of a book, a camellia worn as a sign of recognition… From Dumas’s The Lady of the Camellias to Proust’s lush botanical descriptions in In Search of Lost Time, the flower punctuates the narrative and gives sensory depth to the characters’ emotions.

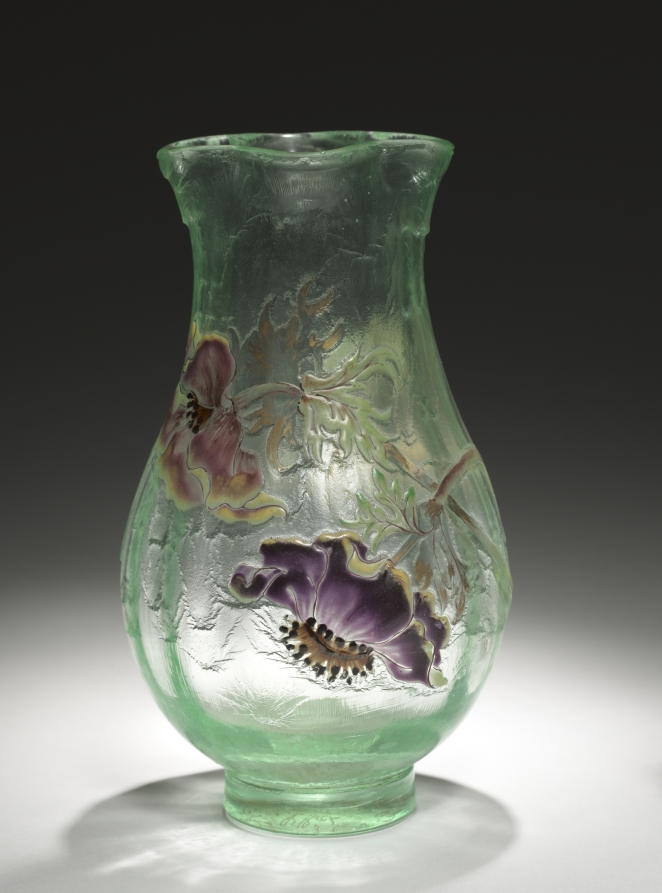

III. Applied Arts and Design: Flowers in Our Daily Lives

The fascination with florals does not stop at museum frames. It has slipped into the most intimate objects of our daily lives. The Decorative Arts have always drawn from the organic to create harmony.At the end of the 19th century, Art Nouveau pushed this mimicry to its peak. Architects like Hector Guimard or glassmakers like Émile Gallé did not merely draw flowers: they ensured that wrought iron or crystal curved like a lily stem in the wind. The house itself became a garden of glass and steel.This tradition continues in high jewelry, where diamonds mimic dew on a gold petal, and in textile design, where floral patterns (from Paisley to Liberty) continue to bloom on our clothing, proving that our need for nature is universal and timeless.IV. Conclusion: Cultivating Our Aesthetic GardenTo trace the history of art through the prism of the flower is to understand the evolution of human sensitivity. Whether it is a warning of mortality, a scientific tool, a poet’s cry, or a parlor ornament, the flower remains the most direct link between the earth and the spirit.

In this “Flowers and Art” category, we invite you to dive into detailed narratives, discover forgotten anecdotes about the great painters, and rediscover the texts that have made the flower an eternal queen

Explore all our articles